Reinterpreting Literary Studies: Beyond Thomas Babington Macaulay’s “Minute on Indian Education (1835)”.

English literary studies, as a discipline, is fundamentally passé and is in a state of impasse; the sooner we realise this, the faster we can move on and make an epistemic shift in the Humanities in defining what constitutes “literari-ness”; most importantly – it has little relevance and serves no purpose in the Indian context because the Indian literary tradition – which is thousands of years old – cannot be determined by a British literary tradition, that at the most, is still quite recent. It is incredibly problematic that we refer to British cultural motifs in order to talk about our desires as an Indian society. We have to be willing to recreate a literary tradition that refers to the Indian literary-Sanskritic past.

I will use an example of a 16th century text to elucidate my point; in Tûlsidásá’s Awadhi (Hindi) version of Valmiki’s Ramayana, Sri Ramacharitmanas, there is a passage in the introductory chapter, where the Bhakti poet draws attention to the literary processes that he used; and he writes:

For the gratification of his own self, Tûlsidásá brings forth this very elegant composition relating in common parlance the story of the Lord of Raghus, which is in accord with the various Puranas, Vedas and the Agamas (Tantras), and incorporates what has been recorded in the Ramayana (of Valmiki) and culled from some other sources.

In the above extract, we learn about poetic self-intellectual gratification; and the freedom that the poet took in using “common” language to talk about a sacred text; in a self-referential moment, Tûlsidásá also refers to the fact that he used a number of primary sources to arrive at his own poetic text.

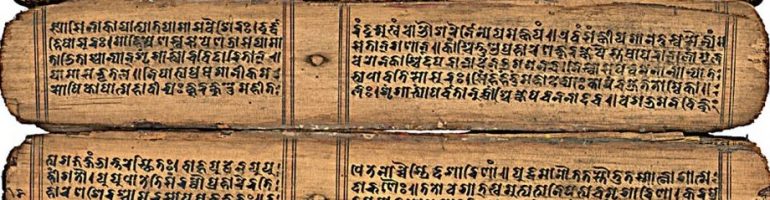

Literary studies, as a discipline – at least, in the Indian context — needs to embrace this pre-print manuscript culture that has existed in the Indian literary tradition for thousands of years. Why have we allowed ourselves to be coerced into a kind of a forced amnesia?

Even if we accept that the scholarship on print culture within the South Asian context is still in its nascent stages, it does not explain as to why there is very little mention of India’s pre-print literary tradition, and even if there is, it is conflated with popular-folk culture. In the colonial Indian context in the nineteenth century, Anindita Ghosh argues, one has to take into account the existence of “significant preprint literate [performance based] communities” which continued to operate in the presence of print as “print sustained earlier reading and writing traditions.” (Anindita Ghosh, “An Uncertain ‘Coming of the Book’; Early Print Cultures in Colonial India.” Book History 6(2003)). Book historians argue that in a post-print culture in colonial India, different kinds of public spheres emerged, and these did not necessarily exist in mutual harmony, as there was a constant shift between print and orality. But eventually, as the editors of India’s Literary History state, it was “printed prose which became the principal vehicle for a literary modernity in colonial India.” (India’s Literary History. Essays on the Nineteenth Century, ed. Stuart Blackburn and Vasudha Dalmia (New Delhi: Permanent Black, 2004)). What becomes evident is that book historians have an acute sense of apathy towards India’s literary-manuscript culture.

We, though, need to ask a fundamental question: what exactly constitutes literary studies? Why exactly should we keep on rehashing texts that have been examined, and deconstructed – ad nauseam? What do I – as a reader and as one engaged in participating in this practise – gain through this act? Literature reflects on a vast repertoire of experiences, and creates cultural motifs which define identity and that in turn becomes ontological to a society. We need to question as to what academic institutions offer us in terms of providing us with an education in literary studies. As of now, by being a participant in the Literature department, I have been systematically taught to erase what is central to my identity and my cultural past as an Indian.

Towards a diasporic New-World order of a global 21st century. Retrieving the cultural heteroglossia of our pasts.

We should desire to arrive at new interpretative methods of analysing the colonial past and the diasporic present. The focus is on retrieving primary texts that would critique and displace the existing, dominant theoretical models.

Postcolonial theory assumes that the dialectics between the civilizing mission of the Empire and the colonial wanna-be subject affect both the colonial discourse/ power that aims to keep the subject under a panopticon method of surveillance, and the subjugated native. There is an eternal desire to create perfect natives who always fall short in this act of mimicry and this act of becoming is never brought to a conclusion. The onslaught of the superior western powers is so rampant and absolute that it enables for the perpetual erasure and denigration of the “native” cultures; and as the foremost postcolonial theorist argues, “[t]he line of descent of the mimic man can be traced through the works of Kipling, Forster, Orwell, Naipaul, and to his emergence, most recently, in Benedict Anderson’s excellent work on nationalism, as the anomalous Bipin Chandra Pal. He is the effect of a flawed colonial mimesis, in which to be Anglicized is emphatically not to be English.” (The Location of Culture, pp. 85-92) I would also position Homi Bhaba himself within this list of “mimic men” – whose scholarship in itself is an “effect of a flawed colonial mimesis.”

If only Homi Bhaba had read a few “native” texts, had lived in Bengal, knew Bengali and imbibed a Bengali literary tradition – and had not been so busy reading Freud, James Mill, Charles Grant and the ever-so-famous Thomas Macaulay, and sucking up to western academia ad nauseum – maybe, postcolonial theory would not be in the Sisyphean chaos that it is presently. And the tales that we are taught in graduate school, in a rote-like manner – about the civilizing gaze of the West – might never have been told. Homi Bhaba, indeed, is a funny man – a very comic writer.

To understand the colonial past, it is more relevant to read someone like Bankim Chandra Chatterjee (1838-1894), who wrote a paper titled, “A Popular Literature for Bengal” and presented it to Bengal Social Science Association in 1870.

As long as the higher education continues to have English for its medium, as long as English literature and English science continue to maintain their present immeasurable superiority, these will form the sources of intellectual cultivation to the more educated classes. To Bengali literature must continue to be assigned the subordinate function of being the literature for the people of Bengal, and it is as yet hardly capable of occupying even that subordinate, but extremely important, position.

…

I believe that there is an impression in some quarters that Bengal literature has as yet few readers, and that the few men in the country who do read, read only English books. … But it is not altogether correct to entertain the idea that the absolute number of purely Bengali readers are in reality so few. The artisan and the shopkeeper who keep their own accounts, the village zemindari and the mofussil lawyer, the humbler official employé whose English carries him no further than the duties of his office, and the small proprietor who has as little to do with English as with office, all these classes read Bengali and Bengali only; all in fact between the ignorant peasant and the really well-educated classes.

And we Bengalis are strangely apt to forget that it is only through the Bengali that the people can be moved. We preach in English and harangue in English and write in English, perfectly forgetful that the great masses, whom it is absolutely necessary to move in order to carry out any great project of social reform, remain stone deaf to all our eloquence.

The reformist, civilizing gaze of the West – did not necessarily create partial colonial subjects, who were perpetually caught between the desire to be and not being able to become. There would have been “great masses” of natives who simply shrugged off the West and the civilizing gaze, even as James Mill and Charles Grant were busy theorising about them. The onslaught of Difference created new subjects who carried with them the past alongside certain aspects of the new. The refusal to allow themselves to be moved into complete subjugation or the impossibility of doing so – because of their blind adherence to socio-cultural-religious beliefs – allowed for the perpetuation of old cultural systems. These archaic practises of the natives that refused to be buried and still continued even in the face of stiff socio-intellectual opposition, allowed for the sustenance of a diverse, heteroglossic society.

The multi-textual nature of religious-manuscript culture in the early realm of print in colonial India.

This is a call for a collection of essays/primary texts that looks at early colonial-imperial print and the nature of Orientalist scholarship, based on religious texts, that emerged with Sir William Jones, post-1780s. Manuscripts of the Hindu religious texts were often transferred onto print; but what exactly were the processes involved? How did native-brahmins look upon it as they assisted the Britishers in making the shift take place from a manuscript culture to a realm of print technology?

In 1825, Graves Chamney Haughton, a professor of Hindu Literature in the East India College, published an out-of-print text, William Jones’s translation of the Sanskrit Manava Dharma Shastra or the Institutes of Manu. Haughton’s prefatory note states that it was a new edition of Sir William Jones’s translation; he writes that in his text “the version of the learned translator has been carefully revised and compared” and that discrepancies would have been a result of the “variety of the manuscripts consulted by Sir William Jones.”

In 1794, the British government of India had Jones’s Manava Dharma printed; Sir William Jones, writes in his preface about the processes involved in collaborating with the Brahmins in writing the text:

…[A]nd the brahman, who read it with me, requested most earnestly, that his name might be concealed; nor would he have read it for any consideration on a forbidden day of the moon,… so great, indeed, is the idea of sanctity annexed to this book, that, when the chief magistrate at Benaras endeavoured, at my request, to procure a Persian translation of it, before I had a hope of being at any time able to understand the original, the Pandits of his court unanimously and positively refused to assist in the work; nor should I have procured it at all, if a wealthy Hindu at Gaya had not caused the version to be made by some of his dependants.

Sir William Jones, operating within the ideology of eighteenth century print culture that associated print with truth, assumed that the technology of print had the power to transform a pre-modern, Indian scribal culture into western modernity. But this equation between print and truth was not intrinsic to letterpress technology as till the early decades of the eighteenth century there was a suspicion of the printed word. In The Nature of the Book: Print and Knowledge in the Making, Adrian Johns draws attention to assumptions about print culture, stating that what we “often regard as essential elements and necessary concomitants of print are in fact rather more contingent than generally acknowledged. Veracity in particular is … extrinsic to the press itself, and has had to be grafted onto it.” A printed book could never be trusted to be what it claimed. Johns claims that in the seventeenth century, piracy and plagiarism were dominant fears. It was a matter of routine that books could be considered dubious; therefore, it was impossible to trust any printed report. Pirate editions of Shakespeare, Donne and Sir Thomas Browne were liable to egregious errors, and so was Sir Isaac Newton’s unauthorized publication of Principia and the first scientific journal, the Philosophical Transactions. It was only in 1760 that the first book was printed without any errors.

The question to ask is thus: did natives operate within a different parallel epistemic world where multiple manuscripts of the same text were seen as legitimate; moreover, why were the brahmins not necessarily keen to see their names on print, but neither were they hesitant to transfer a manuscript culture onto print? These early decades of colonial print can throw more light on the nature of religious-manuscripts that existed in India, before the advent of print in India.

The collection will be published by Lies and Big Feet, an independent publishing house in India (www.lieandbigfeet.wordpress.com). It is a collaboration with Facsimile: a Center for early print. 1780-1820 (www.colonialprint.wordpress.com).

A turn in theory: towards a 21st century notion of post-theory.

This collection of essays will look at notions of subjectivity, self and identity that critique the dominant theoretical movements of modernism and postmodernism.

Before the advent of western modernity, pre-colonial British India had a culture that was located at the cusps of an Islamic-Hindu-pluralistic identity; it existed in a state of perpetual contradictions, ambiguities and paradoxes. For example, if we look at the specificities of how people lived – engaged with society and the institutions of the state and local governance, we will be unable to catalogue the sheer diversity of life. This was the ultimate postmodern condition which can be defined as a state of being; at the same time, the western world was reeling under grand modern narratives. In retrospect, the arrival of the East India Company, along with the juggernaut of Western civilization, should be considered as being one of the numerous socio-civilizational changes that had taken place in the Indian subcontinent.

The obsession that Western theory has with clearly schematized theoretical movements and periods is nauseating and obviously flawed; it rests on making grand assumptions that the postmodern necessarily follows the modern – in a trans-global fashion; at what moment, in the history of the world, did European theory and artistic movements be representative of the World, and for that matter, why are we – those in the non-western worlds – perpetually, in a Sisyphean manner, condemned to emulate and desire those theoretical agendas that predominantly represent Europe? It would be more appropriate to say that modernism and post-modernism coexisted alongside numerous unnamed and undefined socio-structural, religio-secular-cultural states.

What we forget is that absolute narratives create homogenous subjects, citizens and sanitized nation-states; a condition that leads to a deadening of sensibilities, and the death of the humanist subject.

Unravelling the threads of “revealed knowledge”: deconstructing gender in Hinduism.

This collection will examine the nature of religious texts and how oppressive gender norms are inscribed within them. The focus is to read religious texts as “texts” within a literary-feminist interpretative parameter, and in the process, make it possible to re-write sections of these texts which are misogynous/ caste-ist.

Feminist scholars can cry themselves hoarse in trying to understand the nature of institutionalised misogyny that permeates all aspects of civil, social and religious life and has been seen as the status quo since times immemorial. On similar lines, development theorists and economists have tried to address how poverty works in order to alleviate it. But if we refuse to acknowledge that religion which is the bedrock of all societies- is the perpetrator in enabling this kind of gender-class oppression – then it is a losing battle that feminists and economists wage as they analyse the origins of social inequalities.

And so – whom should we blame? For example, if the Upanishads articulate a sense of heightened machismo – and the sole purpose of religious institutions is to perpetuate and propagate this particular brand of religion, apart from also referring to ways of achieving Nirvana, – then this sense of misogyny will exist in an a-historical manner and there is nothing that the secular state can do to undo the entrenched misogyny. For example, in the Aiteraya Upanishad, it is written:

In man indeed is the soul first conceived. That which is this semen is extracted from all the limbs as their vigour. He holds that self of his in his own self. When he sheds it into his wife, then he procreates it. That is its first birth.

…

She, the nourisher, becomes fit to be nourished [protected]. The wife bears that embryo (before the birth).

Women are seen as passive – only of use in procreation. And this is the recurring trope which dominates all religious texts. No one has the authority to question the nature of “revealed knowledge” which determines socio-cultural values.

If we look at how a religious institution works and I cite the example of a global institution like the Ramakrishna Mission – which considers itself as progressive and modern in its outlook – despite the enormous charitable work that it has done – not a single peep has emerged from the hallowed corridors of this religious order about the misogyny within Hinduism and neither has it ever attempted to address the fact that the very bedrock of its existence –that the religious mantra it preaches – is laden with misogyny. Any institution that propagates the Hindu religious texts – is complicit in acts of perpetuating misogyny in an institutionalised manner. How is it that no one ever holds them accountable for spreading such kinds of hate-speech? Why is it that feminists and economists and development scholars never analyse how these religious institutions work in creating a social order which entrenches misogyny in the psyche of all citizens?

Re-transcribing Hindu religion; locating gender in the literature of the Upanishads and the Vedas.

This collection aims to construe Hindu religious texts as literature, and examine them within a gendered analytical framework. What prevents us from examining the Upanishadic or the Vedic texts within a literary or a gendered perspective? If the basis of religion is “revealed knowledge,” which was made evident to men – then is it not obvious that these notions of the Absolute Being would but be defined within gender inflected terminologies?

Let me explain with an example from an Upanishad. In the Aitareya Upanishad, the first stanza reads in the following manner:

“Om! In the beginning this was but the Absolute Self alone. There was nothing else whatsoever that winked. It thought, ‘Let Me create the world.’”

We have to keep in mind that the Vedic texts are partially truthful – they are correct in their explanations on the notion of Absolute Consciousness which becomes matter, and there is no gender ascribed to this Absolute Being. The “Absolute Self” is denoted within gender neutral terms and is referred to as “It.”

But there is a slippage which occurs in the Vedic texts, making these texts suspect: it reveals the fact that those who were writing about this kind of revealed, divine knowledge were men and their interests are evident in how the notion of Absolute Consciousness is defined and described. In the same Vedic text, we will find gender specific characteristics of the Absolute Being. The second stanza of the Aitreya Upanishad reads in the following manner:

He created these worlds, viz. ambhas, marici, mara and apah. That which is beyond heaven is ambhas. Heaven is its support. The sky is marici. The earth is mara. The worlds that are below are the apah.

A shift occurs whereby, “It” becomes “He”: and we all assume, and accept, that the Absolute Being has to be male. To follow this statement to its conclusion, we can state that as the Vedic texts equate the “Absolute Self” with the masculine, men are seen as being agents; in the second part of the Aitreya Upanishad, the first stanza reads: “In man indeed is the soul first conceived”; the implication is that men are agents in determining the birth of children while women are mere passive receptacles.

Biological sciences make use of these dichotomies, and feminists have critiqued how biology (which should be an objective science) makes use of the dominant trope of the “passive” female egg and the “active” male sperm. It is a notion that was also used by Aristotle and by St. Thomas (M.C. Horowitz, 1976, Aristotle and Woman).

There is no attempt by any religious institution to undress these entrenched misogyny that exists in Hinduism; and these dominant mainstream institutions simply reiterate the status quo. If we pick up a random text on religion that has been published by a well-recognized, religious institution, like the Ramakrishna Mission (that is seen as epitomising modern Hinduism), we find a similar trope operating as the subtext.

In How is a man Reborn, a short text that was published in 1970, by Advaita Ashrama, the publishing house of the Ramakrishna Mission, Swami Satprakashananda makes use of the same above mentioned dichotomy (pp.43-48); he cites instances from the Chandogya Upanishad, the Brhadaranyaka Upanishad, one Dr. Sturtevant, the Aitareya Upanishad and Sankara to prove the same point, whereby women are seen as passive agents whose only role in society is to procreate while men and sons do all the active work.

The collections of essays will focus on ways to rewrite the Hindu religious texts, and read them as literary artefacts, and in the process, make them gender neutral.

This is a collaboration with Open Windows: A feminist research center (www.aresroucecenter.wordpress.com). The collection will be published by Lies and Big Feet: an independent publishing house (www.liesandbigfeet.wordpress.com)

Reading religious texts as literature. Re-writing religion; undoing the misogyny.

This collection will look at literary-feminist interpretations/ re-readings of Hindu religious primary texts.

The focus of literary studies needs to change; and we, who live in the erstwhile colonies, need to talk about literary studies outside the dominant referential analytical framework: i.e. on how, once-upon-a-time, the discipline of English was part of the “imperial mission of educating and civilizing colonial subjects in the literature and thought of England, a mission that in the long run served to strengthen Western cultural hegemony in enormously complex ways.” (Gauri Viswanathan, Masks of Conquest. Literary Study and British Rule in India (New Delhi: Oxford University Press) According to her, “a great deal of strategic maneuvering went into the creation of a blueprint for social control in the guise of a humanistic program of enlightenment”; and the English literary text functioned as a surrogate Englishman in his “highest and most perfect state” becoming a “mask for economic exploitation.”

When we ask the question as to what comprises a literary text, we should be willing to venture into territories that have not been examined before and this would allow us access to a wide variety of primary texts. I would argue that the focus of literary scholars should be on re-reading religious texts and undoing the underlying misogyny. Religion affects all aspects of our lives – and if we want a change to take place in the realm of the public around the world, we need to dismantle/re-write the existing religious texts. If we don’t, then the very safe, glass-haven, spaces of academic institutions can just be blown apart by religious fundamentalism in the very near future.

If we examine the Upanishadic texts, we realize that they are composed out of a series of narratives, which make use of numerous literary techniques.

For example, in the Aiteraya Upanishad, there is a story about creation:

Om! In the beginning this was but the Absolute Self alone. There was nothing else whatsoever that winked. It thought, ‘Let Me create the world.’”

It created these worlds….It thought, ‘These then are the worlds. Let Me create the protectors of the worlds.’ Having gathered up a (lump of the) human form from the water itself, It gave shape to it.

The Upanishadic text moves on and talks about the five senses and the need to nourish and sustain the body, which has been formed out of spirit:

It [The Absolute Self] thought, ‘This, then, are the senses and the deities of the senses. Let Me create food for them. …

This food, that was created, turned back and attempted to run away. It tried to take it up with speech. It did not succeed in taking it up through speech. If It had succeeded in taking it up with the speech, then one would have been contented merely by talking of food.

And the narrative continues in this semi-humorous manner; where The Absolute Self analyses the need for “food” and the process which would have been involved in consuming the food; the analysis has a to-and-fro movement which borders on being self analytical. Humour lies in the whole situation where the Absolute Self examines the nature of “food” that the newly created human body has to consume; “food” tries to run away and “speech” attempts to run after it but fails. The verse concludes in a self-deprecating manner, by saying that this failure was needed because if “speech” had succeeded, then we would have been satisfied by talking about food.

We cannot ignore the fact these texts would have reflected the values system of that time period, and this explains the misogyny that is the dominant rubric within which the text is written. There are verses in the Aiteraya Upanishad which call out the very specific gender roles that are involved in the family structure; women have to be mothers to sons and that is the only role that can be ascribed to them:

She, the nourisher, becomes fit to be nourished [protected]. The wife bears that embryo (before the birth). He (the father) protects the son at the very start, soon after his birth. That he protects the son at the very beginning, just after birth, thereby he protects his own self for the sake of the continuance of these worlds. For thus is the continuance of these world ensured. That is his second birth.

As literary scholars, our focus should be on not only interpreting these texts within a literary framework of analysis, but also dismantling these misogynous renditions of the Upanishadic texts. If religion is seen as embodying revealed knowledge, that is immutable, then we, as literary scholars, need to change that perspective.

The seriousness of this work should not be undermined; religion dictates all aspects of our lives – public, private, institutional and secular. The misogyny in religion (that operates in an a-historical manner) spills over onto our societal value systems that undermines the secularism in our everyday lives.

Texts do not work in isolation; they emerge from and work within social systems. Why should the Upanishadic texts, that were written thousands of years ago, still dictate our social behavior in the present?

and more:

Academic freedom and censorship in a post 9/11 United States. (http://wp.me/P3UukW-S)

Gender troubles: the unstable text in Hindu myths and epics and the hypocrisy in Hindu dharma.(http://wp.me/P3UukW-15)

Towards a Diasporic Imagination of the Present. (http://wp.me/P3UukW-Z)